As parents in Australia, you are likely weighing options for your children’s schooling, perhaps drawn to the promise of public education’s accessibility and structure, or curious about alternatives like Classical Christian Education.

But what if the public education system is not the neutral ground it is often portrayed as? What if it’s shaped by a deliberate worldview that sidelines timeless truths in favour of shifting sands? This article explores that reality, rooted in historical facts and educational philosophy.

Our central thesis is that modern public education, including in Australia, bears the indelible mark of American thinker John Dewey (1859–1952), whose ideas of pragmatism and relativism had global reach. These weren’t accidental imports; they were strategies to reshape society, removing Christianity and God from classrooms.

The result? A system that, far from neutral, functions as a neo-religion grounded in human-centred evolution and change, fostering confusion rather than clarity. In contrast, Classical Christian Education anchors children in immutable biblical principles, offering a stable compass for life.

This shift was not gradual or organic. It crystallised in a profound cultural chasm around 1963, marking the end of an era rooted in Christian foundations and the dawn of a “post-Christian” paradigm. Drawing from historical analyses of American education (which profoundly influenced Australia’s systems), this pivot engineered new foundational assumptions about reality, knowledge, and the good life.

Pre-1963, education balanced divine absolutes with reason; post-1963, it elevated subjective desires and state-driven narratives, paving the way for today’s relativism. Understanding this divide illuminates why public schools today prioritise “global citizenship” over godly heritage, and why alternatives like Classical Christian schooling reclaim the old, time-tested ground.

The Christian foundations of early education (and their erosion)

Australia’s public education system did not emerge in a vacuum. It draws heavily from 19th-century models, particularly those from the United States and Britain, where schooling began as a Christian endeavour. Early colonial education in Australia, like in America, was explicitly faith-based. The first schools, often run by churches, used the Bible as a core text to instil moral character and literacy. Noah Webster’s 1828 dictionary, influential in early American (and thus Australian colonial) education, included Bible verses for word explanations, ensuring children grasped divine truths alongside language.

This Christian foundation persisted into the early national era. In America, 97% of the Founding Fathers were practicing Christians, and 187 of the first 200 colleges were Bible-teaching institutions. Harvard’s entrance required strong biblical knowledge. In Australia’s early schools of the same era the Bible was central.

That started to change in the 1830s, when humanist Horace Mann (1796–1859) pushed for state-supported schools excluding scripture. Mann, influenced by Prussian models, imported socialism-tinged uniformity, aiming to standardise education without religious “bias.” By 1859 Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (November) collided with Mann’s reforms (October) and John Dewey’s birth (August), igniting a shift.

Darwin’s theory, praising constant change as the “highest good,” bolstered relativism and positivism, i.e. ideas that nothing is absolute, only evolving human perceptions.

This undermined Christianity’s absolutes: God as unchanging Creator, original sin, and salvation through Christ. Evolution implied no fall from Eden, no need for redemption, man as his own god.

As one historical analysis notes,

“Since man was considered to have evolved from the slime, there could have been no fall of man… Thus evolution strikes at the root of Christian faith.”

In Australia, this seeped in via British influences and American exports, eroding godly heritage by omission. By the early 20th century, schools omitted Christian testimony in history and taught science as “chaos” rather than divine order.

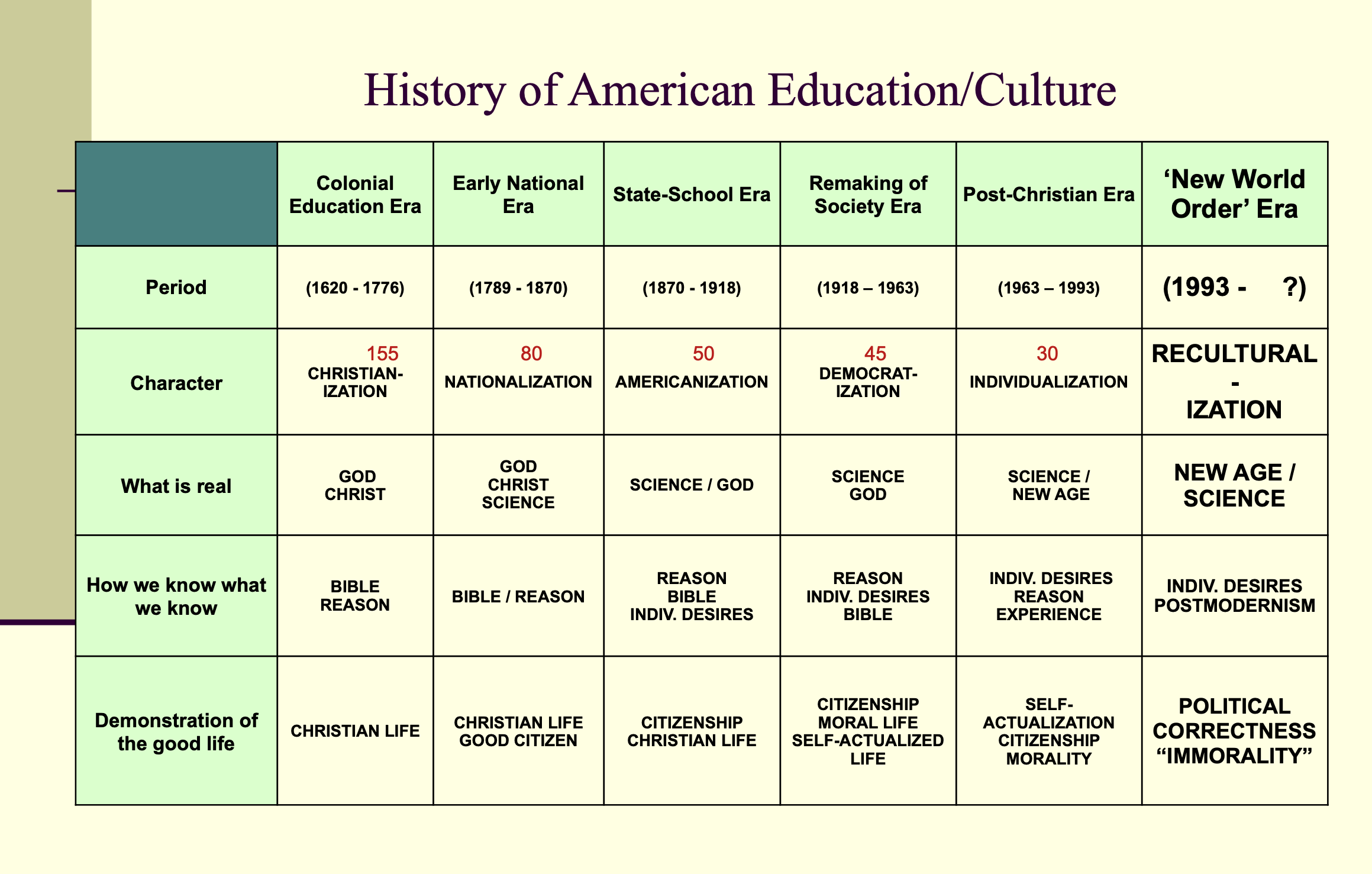

The arc of educational history reveals distinct eras, each with shifting assumptions about reality, epistemology, and ethics. In America’s colonial and early national periods (1620–1870), the focus was “Christianisation” and “nationalisation”. What is real? God, Christ, and science as His creation. How do we know? Through the Bible and reason. The good life? A Christian life of virtue and good citizenship, blending faith with civic duty.

Australia’s colonial schools mirrored this, embedding biblical literacy as the bedrock of knowledge and morality.

By the state-school era (1870–1918) and remaking of society (1918–1963) – Dewey’s heyday – the balance tipped toward “Americanisation” and “democratisation.”

Reality still included God alongside science, knowledge drew from individual desires, reason, and the Bible, and the good life fused Christian ethics with citizenship and self-moral living. Yet cracks formed: Dewey’s pragmatism began diluting absolutes, preparing the ground for the seismic 1963 divide.

The 1963 Chasm: from divine anchors to subjective sands

The year 1963 stands as a watershed, a clear chasm between old, traditional foundations and a new, engineered worldview. This wasn’t mere coincidence; it aligned with landmark U.S. Supreme Court rulings like Abington School District v. Schempp, which banned mandatory Bible reading and prayer in public schools. These decisions were rooted in the secular humanism Dewey championed decades earlier. The result was an explicit pivot to a “post-Christian era” (1963–1993) of “individualisation,” followed by a “New World Order era” (1993 onward) of “reculturalisation.” These shifts exported to Australia, influencing progressive reforms and national curricula that sidelined faith for inclusivity.

Pre-1963 assumptions were time-tested and integrated:

- What is real? God, Christ, science as harmonious revelations of divine order.

- How we know what we know? through the Bible and reason, providing objective truth tested by logic and revelation.

- Demonstration of the good life: Christian life, pursued through moral integrity, community service, and eternal perspective.

Post-1963, the engineered replacements fractured this unity:

- What is real? Science and New Age spirituality, i.e. materialism fused with vague mysticism, excluding the transcendent God.

- How we know what we know? Through individual desires, postmodernism, experience, indoctrination, and authority (the state and media dictate beliefs, sidelining personal discernment).

- Demonstration of the good life: self-actualisation, wealth, citizenship morality, and political correctness; fleeting fulfilment via personal expression, societal conformity, and enforced tolerance, often veering into “immorality” unchecked by absolutes.

This chasm, per educational histories, transformed schools from faith-nurturing spaces to engines of cultural remaking.

In the post-1963 era, “individual desires” and “experience” replaced Bible and reason, fostering relativism where truth bends to feelings. By the 1990s, postmodernism amplified this: knowledge as constructed narratives, authority from media and state over Scripture. The good life? No longer Christian virtue, but self-actualised autonomy blended with “citizenship morality” (global compliance over godly conviction) and political correctness as the new orthodoxy.

Australia felt this ripple. Post-1960s, NSW curricula emphasised experiential learning (remember that for a pragmatist like Dewey experience is the only source of knowledge),and social studies, echoing the shift. The Australian Curriculum (AC) today promotes “critical and creative thinking” via desires and experience, not biblical reason, mirroring the chasm’s legacy.

John Dewey: architect of the relativist bridge to 1963

John Dewey bridged the pre- and post-chasm worlds, his ideas ripening into the 1963 divide. Dubbed the “Father of Modern Education” by the National Education Association (NEA), Dewey was an atheist and signer of the 1933 Humanist Manifesto, which he largely drafted.

This document rejected supernaturalism for human-centred reality, affirming:

“The universe is self-existing and not created,”

“Humanism believes that man… has emerged as a result of a continuous process.”

Evolution, per Darwin, made God obsolete; values became relative tools for “human needs,” not divine commands.

Dewey’s Democracy and Education (1916) ranks among the 20th century’s most influential and critiqued works for eroding biblical foundations. He ridiculed traditions, Founders’ efforts, and absolute values, calling the Constitution a “stumbling-block.” His premise: “Nothing is constant; the only constant good is change for the good” (positivism). Rejecting absolutes, he measured value by “relative perception based on human desire,” denying God’s unchanging word. Influenced by Karl Marx (ranking Das Kapital as the top book since 1885), Dewey americanised communism via education, lecturing in Soviet Russia (1928) on state indoctrination (!).

In the Manifesto‘s spirit, Dewey redefined religion: no sacred/secular divide, worship as “cooperative effort” for social well-being. Affirmations like “Religion consists of those actions… which are humanly significant” and “A socialised and cooperative economic order must be established” fuelled his vision: schools as labs for self-actualisation and citizenship, untethered from Christ. He opposed Christian faith aids, teaching evolution to mock Scripture, preparing the soil for 1963’s bans.

His legacy: declining absolutes. Children embraced relative answers, serving economic needs over eternal purpose. Founding Fathers warned: elect only God-fearing men for restraint; without faith, desires rule. As John Adams said, “The general principles… of Christianity are as eternal and immutable as… God.”

Dewey’s ideas take root in Australia. The post-1963 fallout.

Dewey’s influence crossed oceans, synergising with Australia’s reforms and amplifying the 1963 chasm. In several states, his principles of experiential learning (“learning by doing”), interdisciplinarity, and dialogue became embedded in STEM and work-integrated programs. A 2022 study interviewing 60 Sydney educators found these fostering “progressive learning,” yet constrained by standardisation that echoes post-1963 authority.

Australia’s AC nods to integration but prioritises disciplines, child-centred evolution per Dewey. Mockler’s 2018 analysis traces historical echoes: Dewey’s experientialism in NSW’s Quality Teaching Framework, but global education reform movements (GERM) narrow it to testable outcomes (read: postmodern “indoctrination” via state metrics). Post-1960s Australian reforms (influenced by U.S. models) pushed New Age-tinged curricula, omitting Christian heritage for “inclusivity.”

Deliberate secularisation mirrors Dewey and the chasm: Bible omission since Mann, evolution’s rise post-1859, culminating in 1960s prayer bans abroad that inspired local shifts. NSW schools, for instance, teach “global citizenship,” aligning with “citizenship morality” and political correctness / self-actualisation via conformity, not Christian life. Dewey’s principles underpin the neo-religion: humanism via relativism, where change trumps truth.

The dangers of relativism: confusion over clarity in the post-chasm world

Relativism (“nothing absolute, all relative”) breeds confusion, and that process intensified post-1963. Dewey’s “evolutionary democracy” infected law, society, economics with individual desires and postmodernism. Without anchors, children view right/wrong as needs-based, not God-ordained, echoing the shift from Bible/reason to experience/authority. This opens the door to total confusion because everything is just as valuable as everything else and therefore nothing makes sense.

Education should instead ground in solid, timeless, immutable founding beliefs. Biblical absolutes orient life; relativism enslaves to Mammon (money, power) via state/media narratives. Dewey’s vision, per Brave New World parallels, raises state-schooled economic servants, forgetting God. In Australia, omission destroys heritage; schools prioritise “new world order” over faith, enforcing political correctness as the good life.

Parents, this is not neutral. It is engineered. Atheist academics like Dewey wanted it: evolution denies sin/salvation, humanism replaces God with self. The system is working as intended: 88% of Christian children deny faith by college.

Classical Christian Education: Reclaiming pre-chasm foundations

Classical Christian Education is the antidote to all of the above, reviving the trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric), infusing a Biblical worldview, and restoring pre-1963 assumptions. Schools like Coram Deo are grounded in God’s absolutes: Scripture as truth (how we know), Christ as reality’s center, Christian life as the good one. Students master facts, reason critically, persuade eloquently. All oriented by faith, not desires.

In Australia, schools via the Association of Classical Christian Schools adopt this, emphasising virtue and heritage. Unlike public relativism, we build resilience: timeless ethics amid change. Research shows such models boost critical thinking, moral clarity, preparing children not just for jobs, but eternity.

A call to discernment

Public education’s Deweyan roots and 1963 chasm are not neutral. They are a deliberate pivot from God to man, fostering relativism’s fog.

Parents eyeing Classical Christian alternatives should consider this question: will your child navigate life by shifting desires or eternal rock?

Investigate local options. Reclaim your role as primary educator:

These commandments that I give you today are to be on your hearts.

Impress them on your children. Talk about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road, when you lie down and when you get up.(Deuteronomy 6:6-7)

Australia’s future hinges on bridging back to the chasm’s other side.

Parents, start here.

About the author

Corrado Fiore is an IT Strategist and a long-time all-round contributor at Coram Deo.

Sources and references

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120615052413/http://www.christianparents.com/jdewey.htm by the late Larry A. Rice

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120127110209/http://www.christianparents.com/jdewey2.htm (Dewey’s anti-Christian pedagogy).

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120911043730/http://www.christianparents.com/jdeweyfaith.html (Dewey’s A Common Faith and secular “common schools”).

- https://institutefc.org/the-collapse-of-american-education-pt-6-a-godless-revolution-in-the-classroom

- https://answersingenesis.org/public-school/failure-john-dewey/

- https://davidfiorazo.com/2013/02/the-nea-agenda-how-john-deweysocialism-influenced-public-education/ by David Fiorazo. The author covers Dewey’s Marxist ties, Soviet lectures, and deliberate secularisation.

- https://wallbuilders.com/resource/the-founding-fathers-on-jesus-christianity-and-the-bible documents the high percentage of practicing Christian Founders and early colleges’ biblical focus, influencing colonial Australian education models

- https://www.heritage.org/political-process/report/did-america-have-christian-founding

- https://americanhumanist.org/what-is-humanism/manifesto1 and https://web.archive.org/web/20120127110209/http://www.christianparents.com/jdewey2.htm (a critique of the Manifesto)

- “The Synergy between John Dewey’s Educational Democracy and Educational Reforms in New South Wales, Australia” by Mary Helou et al., World Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 9, No. 1 (2022). The author interviewed 60 NSW educators on Dewey’s principles (e.g., “learning by doing”) in STEM and progressive reforms.

- “Curriculum Integration in the 21st Century: Some Reflections in the Light of the Australian Curriculum” by Nicole Mockler, Curriculum Perspectives (2018). The author analyses Dewey’s historical impact on Australian integration and constraints under the AC.

- https://answersingenesis.org/blogs/ken-ham/2025/06/17/why-young-people-leave-church-college and https://www.txcumc.org/news-detail/18568150 were used as sources for the decline in Christian faith among youth.

- “The Tragedy of American Education: The Role of John Dewey” by Institute of World Politics